Erin Mallea

Condition Report, installation view (___) / Blankspace, Pittsburgh, PA, 2024. Photo Credit: Sean Carroll.

Erin Mallea is a multidisciplinary artist exploring microcosms as entry points into larger human and environmental conditions. Working across sculpture, video, photography and print publications, her work scrutinizes cultural relationships to land, place, and time.

Erin’s process is grounded in place-based research and partnerships with individuals, community groups and institutions outside of art spaces. She has worked with biologists, historians, neighbors, community radio, environmental justice activists and more to develop interactive projects, publications and time-based, gallery works. Erin’s work has explored specific contexts such as the internal struggle of a 19th c. utopian community to define itself (Maintaining Utopia, 2018), her grandmother’s attempt to understand and articulate family history (Monument to an Origin Story, 2018), land-use conflicts near her hometown (Refuge, 2019), and the industrial past and ecological transformation of a park beside her former studio (Tree News, Issue 2, 2022).

Erin has exhibited at galleries, museums and DIY spaces including the Laband Art Gallery, Los Angeles, CA; Miller ICA, Pittsburgh, PA; A.I.R. Gallery, Brooklyn, NY, Boise Art Museum, Boise, ID; Melanie Flood Projects, Portland, OR and more. She has sent vibrations from a giant fungus throughout the atmosphere and currently produces Tree News, an experimental publication and event series. She received a MFA from Carnegie Mellon University (2019) and is an Assistant Professor of Art at the Pennsylvania State University School of Visual Art.

Interview with Erin Mallea

Questions by Emily Carol Burns

June, 2025

Hi Erin! Thanks so much for talking with us! Can you tell us a bit about you and where you're from and where, how did you initially become interested in art? How did your early experiences influence you?Thanks, Emily for having me! I grew up in Boise, Idaho and was always making art as a kid. I would spend hours with friends, cousins, or on my own making drawings that were part of larger, elaborate narratives. I’d make up businesses and draw catalogs and plaster my neighborhood with joke flyers, or create silly infomercials and fake documentaries with friends on their parents’ camcorders. I learned how to develop and print film from a neighbor who had a darkroom in their basement. I probably didn’t think of all those activities as “art” at the time, but I always knew I wanted art-making in my life. I became serious about it at the end of high school, and studied painting and drawing in college.

Thematically, my work is influenced by my upbringing in Idaho and the Western US. My work often engages with place, land, and cultural constructs of nature. My grandparents and great grandparents fled dust bowls, immigrated to extractive, remote boom towns that went bust, and were shaped by violent crackdowns on union organizing in silver mines. As I got older, this history gave me an awareness of interconnected relationships between land, extraction, and larger political and economic forces. I also spent a lot of time outdoors with family and friends hiking, biking, birdwatching, camping, etc. There’s a big culture of outdoor recreation in Idaho, and the ideas of wilderness are very present in the state’s cultural consciousness. Idaho (and much of the Mountain West) has a small population and large swaths of federally owned, mountainous forest that are also sites of extraction and violent Indigenous dispossession. I later realized that a lot of the romantic ideas I had absorbed about wilderness were informed by larger histories, American settler-colonial mythologies, and false nature-culture binary.

Were you making drawings and paintings as part of your practice in college, or were you always drawn to other media, like film and video and conceptual work?

Yes, I was making paintings and drawings in college, though I don't paint anymore. Now I mainly draw to explore ideas. Painting and drawing were comfortable to me, and I wasn't exposed to much contemporary art in high school. So when I got to college I quickly became interested in a lot of courses and media beyond painting and drawing. I took a lot of graphic design classes, photography, and minored in art history. Taking a wide range of studio classes, made me excited about conceptual art and artist practices that are expensive in material or approach. I was grateful I was able to explore in that way.

For example, I took an artist book and photography class that exposed me to a range of lens-based and conceptual practices and got me thinking about time, sequencing, pacing, and context as material. I was also motivated by my peers – there was a strong sense of community in the art program when I was a student. Students were organizing events, exhibitions, and things on and off campus. We were inspired by the art history of Los Angeles, like the Womanhouse feminist art program at CalArts, for example. My peers were studying art, art history, photography, film production, literature and more. I was inspired and encouraged to experiment with media. Art making felt like a communal endeavor.

You went to Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Did being in Los Angeles expose you to even more of that type of work, or even just other disciplines beyond painting and drawing?

LA was a great place to study art. It’s a vibrant art city, with a unique history, and built environment. My art history professor's research focused on post-war art and visual culture of Los Angeles with emphasis on subcultures and artist-run spaces outside the mainstream. I didn’t have a lot of exposure to contemporary art before college, so his courses really expanded how I understood art making – as something rooted in place, ideas, community and/or socio-political context. I was lucky to be able to go to museums, galleries, visit private collections, go on studio visits and attend a range of cultural events as part of my coursework, campus job at the university’s Laband Art Gallery, and socially with friends.

Did you feel like when you started investing more of your time and focus into the type of work that you're making now that you sort of hit a vein and you felt like, Oh, this is what I want to be doing? Did that feel like a more natural fit for you?

I always liked the action and process of painting: getting lost in it and visual problem solving. That moment when you resolve something visually is so satisfying. But I didn’t fully feel like a painter. I was always like, “what do I paint?” I felt most comfortable when I was integrating collage, photo, drawing, and different materials together. I ended up taking a lot of other studio courses because they felt more exciting. Looking back I’ve thought, maybe I should have focused more on photography and sculpture in undergrad. Regardless, I’m less interested in working on a singular thing or making a single image. I’ve always been drawn to making works to exist in relation to one another. Whether that’s sculpture, found objects, images, text, video or sites-specific public work: it’s always about what things do together or in context. What are the connections between them, what’s the story they tell, or how do they inform, perform together, or complicate one another?

Do you feel free to move through whatever medium is calling you at the time, or whatever approach the idea is calling for? Have you felt pressure to stay in a particular domain?

Sometimes I wish I made one type of thing or was an expert in one thing. I like the challenge of exploring materials and learning new things. But, because of the way I work, I go through a lot of trial and error and learning curves. As an artist today, there’s the pressure to create a “brand” for yourself that succinctly and coherently ties everything together – your work, life and image are aligned. There’s always that external pressure (grants, applications, the list goes on), but I’m usually not too worried about it. I’m interested in following conceptual and material threads and seeing where they lead. The artist Sister Corita Kent has those famous ten rules for artists and the classroom. One is “Don't try to create and analyze at the same time. They’re different processes.” That helped me. Even though my work is often tied to ideas and language, if I overthink it, I'll never make anything. I enjoy the unfolding and recurring process of making, reflecting, writing, sharing work, pausing, and returning to things.

The project Refuge (2019) is a body of work rooted in Malheur Wildlife Refuge in Eastern Oregon. My dad is an avid birdwatcher, and we would visit to watch the seasonal migration along the Pacific Flyway. I created an artist residency there by organizing a work exchange with biologists in exchange for summer housing. The work that developed is varied materially: a two-channel video work, sculptural works, and an artist book. The works layer land-use politics, family history, and human and animal migration to muse on larger questions of the violent colonial history of the United States, domination and control of the environment, and ecological and generational change. Visually, works are connected by color, material specificity, recurring forms, and explorations of scale. For example, I painted three walls the color of the sky on different days. The blue sky and water of Malheur Lake loops repeatedly in the video and is echoed throughout the space. I played with the intimate scale of an artist book versus a large projection that depicts the vastness of the sky and horizon, and the shape of the fish trap in the video is referenced in different sculptural works.

Refuge, artist book, 140 pages, 2019. Photo Credit: Tom Little.

Refuge, installation view, 2019. Miller Institute for Contemporary Art, Pittsburgh, PA. Photo Credit: Tom Little.

Refuge, installation view, 2019. Miller Institute for Contemporary Art, Pittsburgh, PA. Photo Credit: Erin Mallea.

I recently screened Fieldwork Daydream (2019), the two-channel video from this body of work. It focuses on the refuge’s dark, brutal and Sisyphean attempts to control an invasive fish population. I shot it in 2018, but its relevance to the political situation in the US has only increased – with growing, dehumanizing anti-migration policies, vilification of immigrants, deportations, US imperialism, and the continued rise of white-Christian nationalism. The video tries to ask larger questions about who and what become disposable, who is allowed to move freely, whose success is naturalized, and whose is seen as a threat. Watching this work seven years after I shot it, I’ve been thinking about how a work rooted in a certain time and place or made to be exhibited with specific artworks, can live beyond that, in new arrangements, and in conversation with different pieces.

Fieldwork Daydream, installation view, 2019. Miller Institute for Contemporary Art, Pittsburgh, PA. Photo Credit: Erin Mallea.

Where do your ideas come from? How do you make the decision of what project to do and where to put your energy? When you're embarking on a complex project—creating your own residency at a wildlife refuge— it takes some planning. How do you decide where you will direct your energy and how does that process unfold?

For me, my starting point is often a particular place, situation, image or object. My work is very place-based, and typically I’m inspired or fascinated with a certain dynamic, system, or practice in that place. For Refuge, the starting point was, obviously, the site of the Wildlife Refuge, and I wanted to focus on bird migration. Before my residency, I got funding to attend their annual migratory bird festival. During the festival I went on a tour of the refuge with a biologist, and learned about the invasive carp. I was suddenly transfixed and overwhelmed by the carp trap – the violence and tension between creating a sanctuary for birds at the explicit expense of the fish. The fish were introduced by settlers as a food source after native fish populations were overfished. Now, they’re seen as “trash fish” or “rough fish,” and became a scapegoat for a larger system of human-caused problems. The body of work was trying to work through different layers at the refuge and understand them within a broader cultural context and personal family history.

Images are often a source of inspiration for me. I’m drawn to images that quickly distill human hubris or reveal an inherent contradiction or absurdity. Recently, I returned to found and family images that have been in the back of my mind for years. I never knew what to do with them, but I’m starting to connect them with my photographs, found imagery and (maybe) sculptural work. I still don’t have it resolved, but I feel inspired to start.

It seems like storytelling is a primary force in your work—you're going to places, talking to people and unearthing these stories. Storytelling is a powerful way to talk about ideas—what are your thoughts on this force in your work?

It's funny, because now it seems obvious to me that storytelling is an important part of my work. However, I didn’t always see it that way. Perhaps because in spoken form, I'm a bad storyteller. I bury the lead, I ramble on, I lose my train of thought, the arc is long and meandering. I’m realizing that those are qualities that can be utilized; they’re a more honest depiction of reality in a way. Sometimes, a work is less explicitly narrative on its own, and the story or meaning-making exists in the process or the context surrounding the work’s creation. Other times, the work is communicating a narrative, but that story is fractured, includes many stories within it, or it's inconclusive.

I often become a character in my work, and reveal myself, my perspective and my questions, sometimes more explicitly than other times. My work has a documentary ethos, even when it’s abstract or open-ended. When it comes to documentary, there’s always questions of POV, bias, etc. So I want to reference my shadow in the work.

For me, the storytelling is finding the balance of revealing idiosyncrasies and specificity of place, human actors, or situations while also expanding into larger themes. I’m often exploring cultural relationships to land and time, paradox, finitude, ephemerality, and absurdities of value and logic systems. I’m drawn to situations where systems breakdown, fail, reveal themselves, or mutate. I’m also trying to balance different tones simultaneously: dark humor, futility, hope, and emotional resonances.

Writing helps me understand things, and I incorporate text in my work. A challenge, as you mentioned earlier, is how much text is necessary. What is too didactic that the work loses its poetry or becomes one-dimensional. Where can the work live on its own, without the larger context or background?

To bring up the video Fieldwork Daydream again, it imagines a conversation between myself and the fish to explore empathy, cruelty, control, and the inevitably of transformation and change. The imagery creates a tension between the expansive freedom of the sky and the cage of the water. The second channel shows the fish trap running from start to finish, so the viewer gets a sense of the context. Both videos are meant to loop seamlessly and continuously. What becomes potent as you spend time in the exhibition, are the sounds of the trap mechanisms running over and over. The exhibition also incorporates sculpture and an artist book with photographs, historic images, and writing. The book is more of a deep dive for viewers to better parse the constellation of objects. So there are entry points into the larger context and opportunities for different levels of engagement with the work.

I’m drawn to making works that could be experienced on their own and potentially reorganized into new exhibitions, iterations, or groupings of work. The different components in an exhibition are a smaller story nested within larger ones, and those relationships can shift.

You mentioned writing as part of your process—how does that manifest? In a type of journal or daily practice?

I don’t have a great system. I don’t write daily, and when I write, it’s usually in a mess of disorganized Google Docs... writing is a place where I try to understand what I’m doing. When I’m exploring things in the studio or starting something new, I don’t want to get in my way too much. I want to maintain that exciting studio energy and not overthink it. Then I reflect and write to work through ideas or associations that help me get deeper or clearer. I’m typically working on multiple things at once and the pace and focus shifts. I let some things simmer as I figure out where they’re going. That simmering can take months or years to be honest.

I'm really interested in materials and how they inherently communicate. I'm curious about your relationship to materials. Can you walk us through your approach? How do you decide which ideas to push forward and what materials make sense?

Sometimes I have clear, concise reasons for why I'm doing a certain thing, other times it's more intuitive. Refuge for example, included clay and sagebrush I collected from Oregon and Idaho. I wanted to incorporate the specificity of the place and landscape into the work. A more recent body of work, Permissible Dose, is rooted in the industrial past and present of Pittsburgh, where I’ve lived since 2016. The work incorporates a lot of materials specific to the region’s industrial history. For example, coal I collected from a scraggly, forested hillside that was once a coal mine and a blown glass object I made with the help of the Pittsburgh Glass Center (PGC) – glass was Pittsburgh’s first industrially manufactured product.

Works evolve from material exploration in the studio as well. I’m currently finishing up a second residency at the PGC to continue the work I started in 2022 After my first residency, I wanted to keep exploring mold-making for glass. In December, I started working on molds and created nine new glass objects. I’m still uncovering how the works will live or become part of a larger installation or body of work. They’re an outgrowth of Permissible Dose but have become something new. I also collect and hold onto things (images, found objects etc) that speak to me. I don’t always know why yet, but with time, I will discover why.

There are also practical considerations about what ideas I push forward: what my opportunities are, cost, funding, timeline, etc.

In your bio, you state that you have sent vibrations from a giant fungus throughout the atmosphere, and that's sort of where it ends. So I had to ask, what's going on with that?

That’s referencing a collaborative project with a friend, Jen Vaughn, an artist based in Eugene, Oregon. We met at Signal Fire, a residency that longer exists. The residency connected artists to different wilderness spaces. Our residency was a week-long filmmaking workshop and backpacking trip led by an experimental filmmaker in Oregon. Jen and I became fast friends through Signal Fire, and we wanted to make collaborative work together. The project you’re referencing, Cumulative, Skies, Deep Soils, has had a couple of iterations. It started when we learned about an ancient mushroom growth (honey fungus), in Malheur National Forest, Eastern Oregon, close to my residency at Malheur Wildlife Refuge. It is estimated to be one of the largest living organisms by area, covering 3.5 square miles at an estimated age of 8,650 years. We became fascinated and overwhelmed by its physical scale and age. The honey fungus fruits in the fall for a limited amount of time after the first rain. Most of the year it exists underneath bark or networked underground where you can’t see it. We liked the contradiction of scale. It was everywhere under your feet but difficult to perceive. We made the work collaboratively as we were living across the country from one another. Jen made recordings of honey fungus vibrations using contact mics, and then I partnered with an amateur radio club to send the vibrations and related images via Slow Scan Television (SSTV). SSTV is a mode of image communication that utilizes shortwave radio frequencies to transmit still images. It is slow and specific, taking anywhere from 8 seconds to five minutes for each image to be built from modulating audio frequencies. We liked the idea of collapsing and expanding space and scales, and thought of it as a poetic gesture enmeshing soil and sky. That was the start of the work. From there we developed a sculptural, sound, and light installation that included our SSTV transmissions received and encoded in real time on a small screen during the exhibition.

I enjoy collaborating when I can. Jen is a more materially-driven artist than me. I appreciate working with another artist, because it feels less restricted. It gives permission to explore things I’m interested in but approach it differently than I might alone. Collaborating helps me feel less beholden to certain materials, approaches, and has allowed me to expand and grow as an artist.

Erin Mallea and Jen Vaughn, Cumulative Skies, Deep Soils, installation view, SOIL, Seattle, WA 2022. Photo Credit: Erin Mallea

Erin Mallea and Jen Vaughn, Cumulative Skies, Deep Soils, installation view, Phosphor Project Space, Pittsburgh, PA, 2020. Photo Credit: Erin Mallea

Can you tell us about your ongoing project, Tree News? Can you just tell us a little bit about how it came about and what your goals are for the project?

Tree News is an experimental publication that I started in 2021 with a collaborator, Paper Buck, an artist based in Philly. We went to grad school together, and the project started because we share a lot of interests as artists: investigating where social, cultural, and environmental histories intersect. Tree News focuses on tree and forest stories as entry points into discussions of ecological orientations in art practice, cultural relationships to the natural world, environmental justice, and climate change adaptation. We profile trees, people, places and projects to serve as a platform to share resources, build relationships, highlight community projects, and develop deeper understandings of the world around us. The publication has been produced with a rotating host of contributing artists, scholars, scientists, writers, and land workers.

We’ve produced five issues so far, and I’m starting work on the 6th one now. I love the aesthetic of neighborhood or community newsletters and that was the impetus for the original design. Tree News has also organized occasional events in conjunction with the issues including art and educational workshops, foraging walks, and film screenings.

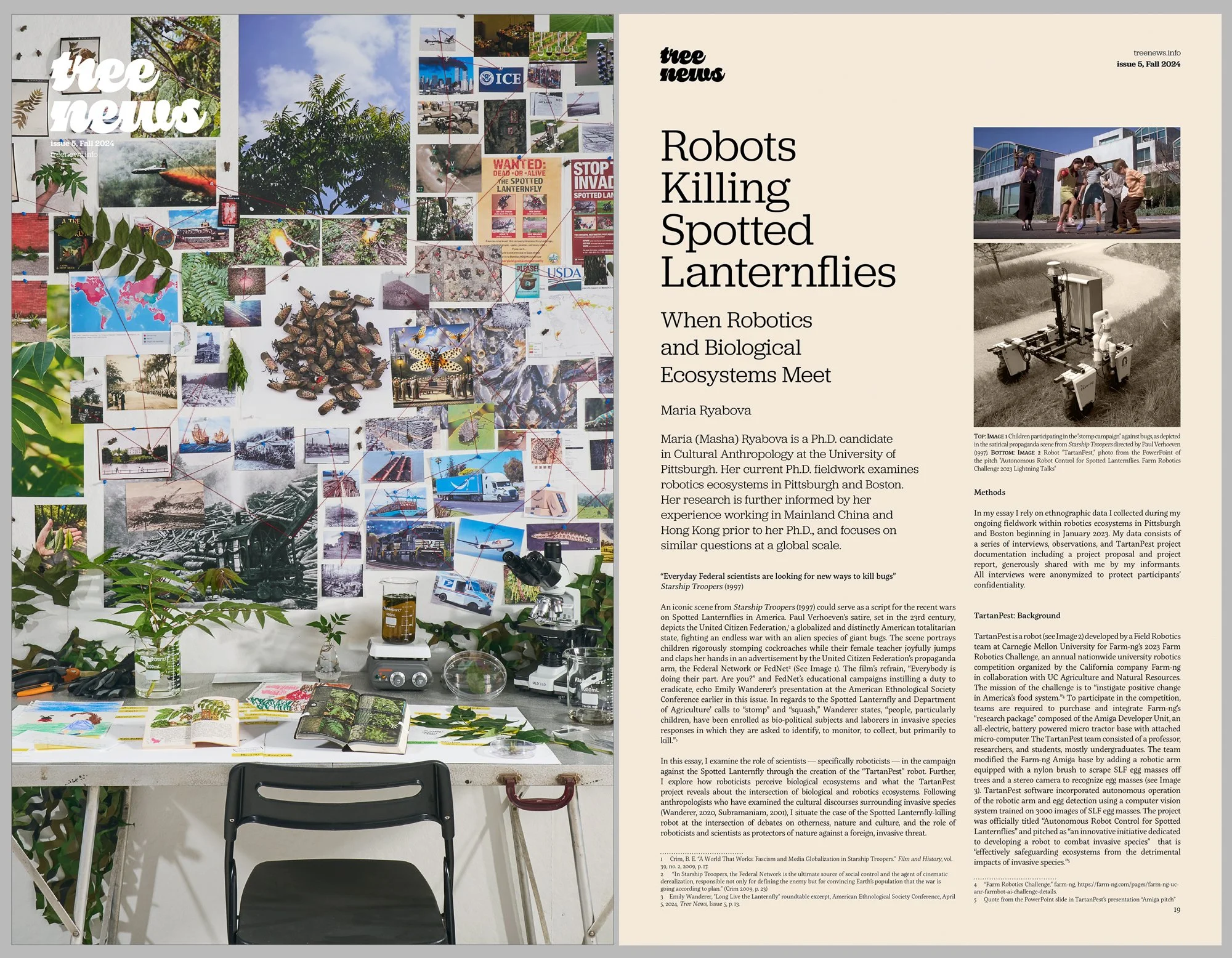

Each issue has a different theme, and the most recent issue tackled a number of larger cultural ideas such as otherness, xenophobia, and colonialism through the lens of the Spotted Lanternfly in Pennsylvania. How did the focus for that issue theme come about?

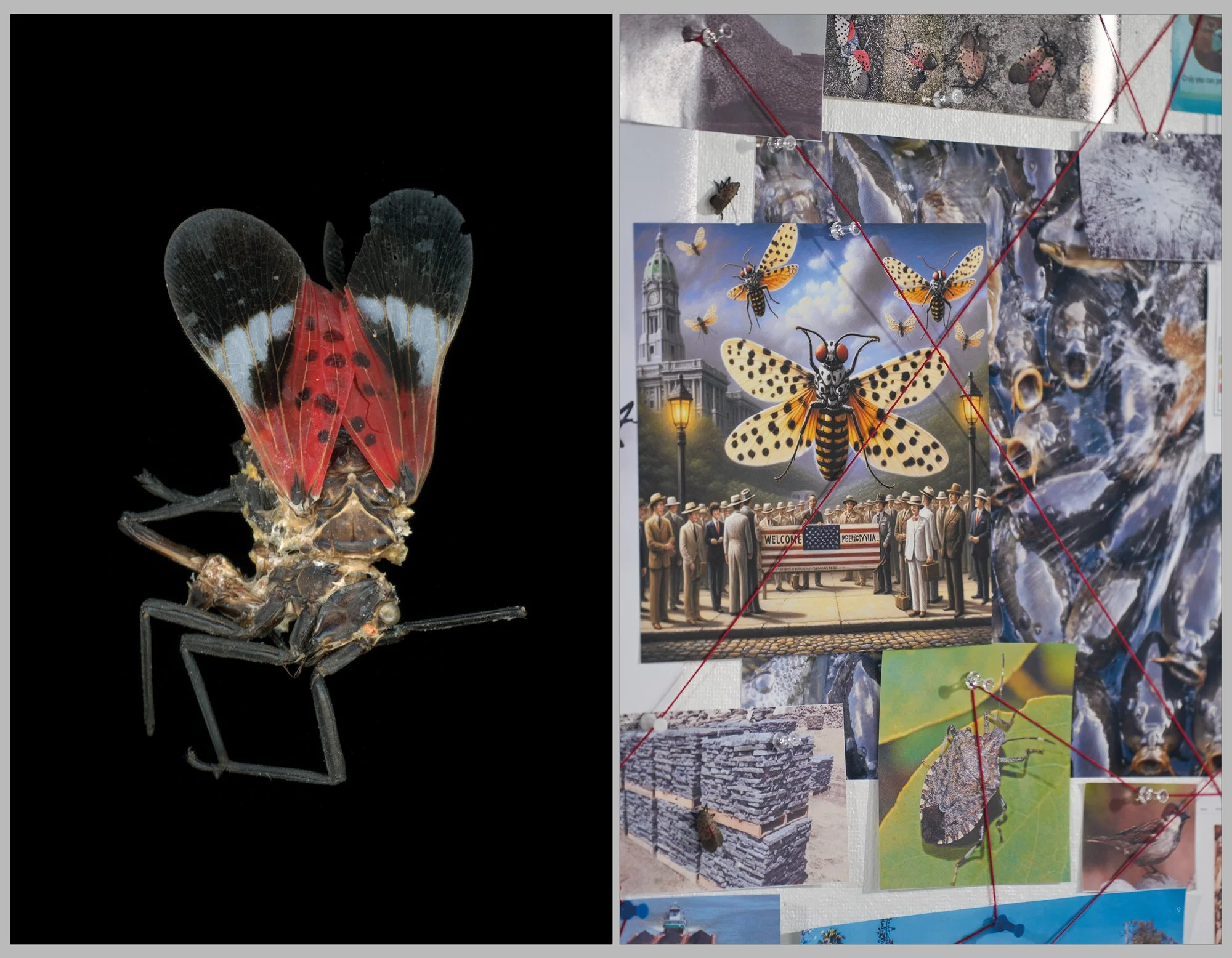

Issue No. 5 (Fall 2024), our most recent issue, was made in a collaboration with Travis Mitzel, a photographer based in Pittsburgh. The issue focuses on the Spotted Lanternfly (SLF), an invasive insect first reported in the US in 2014 in Berks County, PA. Because of my earlier work about the carp, I had been tuned into conversations around invasive species. Travis’s work engages with human and animal relationships, and we’d been discussing the public response to the SLF. There was a huge fear-fueled media and public frenzy throughout the Mid-Atlantic and surrounding states. SLF are native to China and Taiwan and arrived to the US through the global commodity chain: on a stone shipment through the Port of Philadelphia. There was a big USDA PR campaign to squash and stomp that often appealed to a sense of environmental and civic duty. There would be signs in the park saying, “Join the Battle, Beat the Bug.” This campaign became part of the zeitgeist in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, New York, and beyond. There were constant New York Times articles about the insect and why they needed to be killed. I’d see posters all around parks that said, “Scrape, Destroy, Report” and the language felt reminiscent of “See Something, Say Something,” wartime propaganda, or fear-based calls to civilian action.

The rhetoric and how quickly people obliged was fascinating and dark, especially because the research wasn’t conclusive yet. The campaign was built around “saving the forests” but there wasn’t evidence the insect harmed forests at that point. Ultimately, we now know that hardwood trees are not in serious danger. Often, the worry around invasive species is less about biodiversity and more related to commodities or agricultural products. In the case of SLF, the concern is now their impact on grapevines, vineyards, and commercial wineries based on the insect’s impact in Korea and Japan.

The way the insects were villainized, the fervor around killing them, and the shaming if you didn’t want to participate, really resonated with the political rhetoric around immigration at the time. Since the issue was published (Fall 2024), we’ve seen an escalation of dehumanizing, draconian, authoritarian, and unconstitutional actions detaining and deporting people (and children) to horrific conditions – all justified using rhetorical strategies that echo the SLF, “invasion”, and “alien species” (i.e. the administration’s use of the 1798 Alien Enemies Act). The language of pests, hoards, swarms, and pestilence do not exist in a vacuum. Such dehumanizing language has long been a tool to otherize, victimize and justify genocide and violence against human communities.

Tree News No. 5, Fall 2025, cover image by Travis Mitzel (left) and essay by Maria Ryabova (right).

Tree News No. 5, Fall 2025, produced by Erin Mallea and Travis Mitzel.

Issue No. 5, includes an introduction by Travis Mitzel and myself looking at the broader ideas and trying to contextualize the SLF’s arrival. We also discuss Tree of Heaven, SLF’s preferred host tree. Tree of Heaven (ToH) is a much maligned invasive tree that co-evolved with SLF in their native range. The issue discusses the evolution of ToH’s reputation from a valuable “desirable, stately tree” for wealthy Philadelphians to a “Tree of Hell” for those trying, in vain, to remove it from their yards. Issue 5 continues with an excerpt from an interdisciplinary panel at the American Ethnological Society’s 2024 Spring Conference hosted by the University of Pittsburgh. The panel, “Long Live the Lanternfly: Invasive Lifeforms, Extermination Campaigns, and Possibilities for Coexistence”, features Nicole Heller, Ecologist and Associate Curator of Anthropocene Studies, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Kelli Hoover, Professor of Entomology at Pennsylvania State University, Travis Mitzel, Artist and Instructor at Seton Hill University, Noah Theriault, Associate Professor of History at Carnegie Mellon University, and Emily Wanderer, Associate Professor of Anthropology, at the University of Pittsburgh. The panel was organized by Noah Theriault, Nicole Heller and Emily Wanderer.

The issue concludes with “Robots Killing Spotted Lanternflies: When Robotics and Biological Ecosystems Meet,” an essay by Maria Ryabova, a PhD Candidate in Cultural Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh.

The design plays a big role in engaging the viewer—the printed, physical publication is beautiful. You are using design in a way that can make these ideas more accessible to people, because they can sit down with their coffee and engage with the newsletter in a tactile way that feels more mindful than a digital approach.

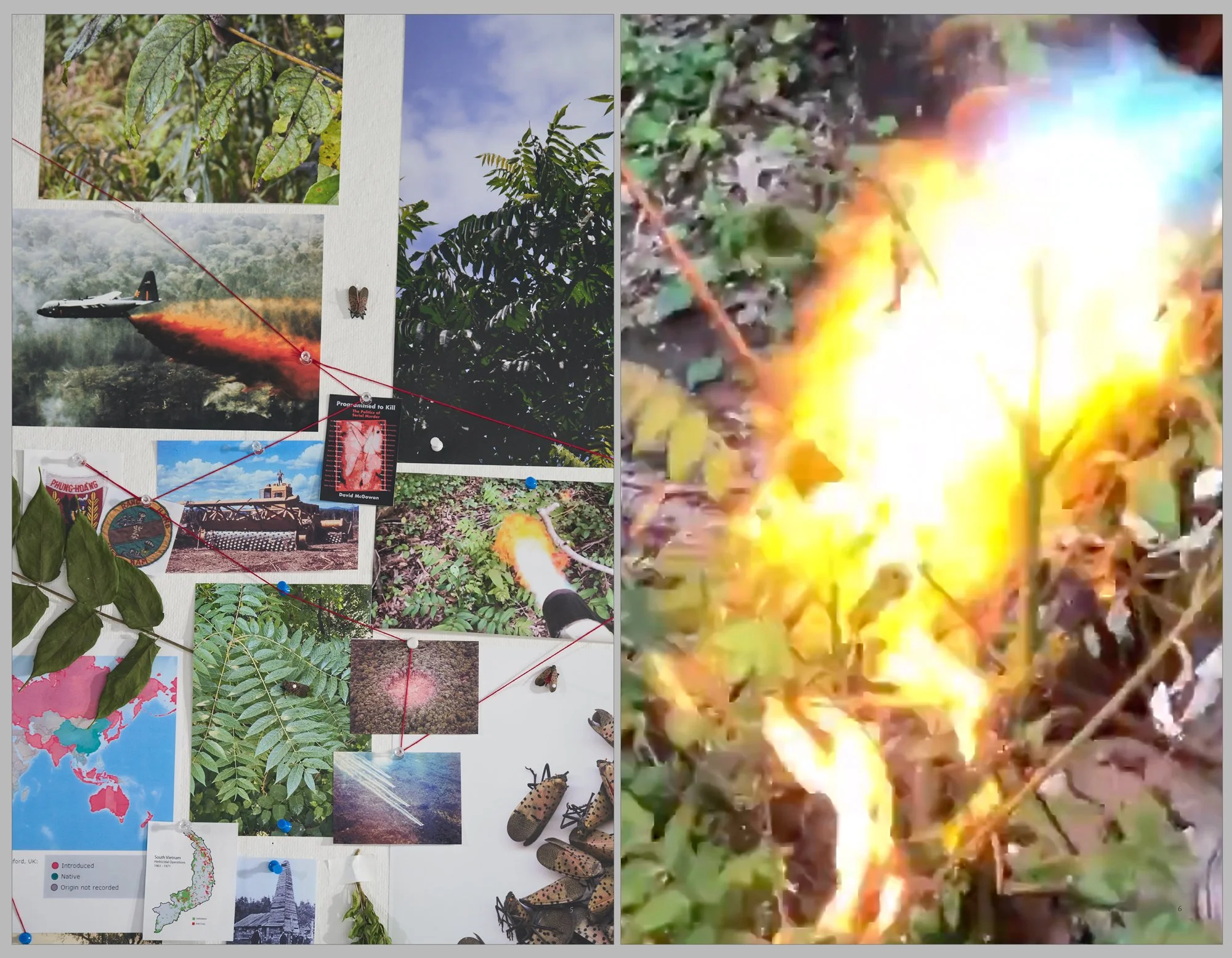

Thanks, it’s nice to hear that from a professional designer! When Paper and I first started Tree News, the issues were simpler in scope and design. The project has grown in ambition, in terms of length, content, imagery, and design. I have a lot of fun with the design and keep pushing that with each issue. I enjoy playing with how everything comes together and seeing the different components in relationship to each other: paper colors, images, layout, etc. It’s a satisfying puzzle. That’s also where my artistic sensibility comes in. The project incorporates “news” in the form of grassroots reporting and storytelling, but I’m not a journalist. As an artist I have more freedom in arranging elements, playing with open-ended or abstract imagery, and emphasizing certain relationships. For example, in Issue No. 5, the introductory essay, “On the Spotted Lanternfly” incorporates photos by Travis and myself. We printed and collaged imagery and objects on his studio wall that create a map of connections and associations between the SLF, ToH, and invasive species management. Travis photographed the wall and those photos were incorporated in the issue. One page in the issue is a large image of a giant, pixelated flame. It was sourced from a YouTube video titled, “Spotted Lantern Fly verses [sic] propane torch”. On the reverse is one of Travis’ photographs that includes the US Army spraying Agent Orange in Vietnam. We wanted to reference that pest control exists in relationship with warfare through the co-development of herbicides, insecticides, and chemical weapons. The orange colors of the flame and the agent orange become visual echoes of one another while pointing to larger themes of control and violence.

We're so used to the 24-hour news cycle, constant breaking news, and dissociating as you’re doom-scrolling. Tree News was not started to be an antidote to how we consume information, but I’ve always loved printed matter and get exhausted with social media and having my attention split in so many ways. I like that Tree News is slow news (once a year). I’d been reading articles, having conversations with Travis, and following the news about SLF for a few years, and by the time we produced Issue No. 5 the mania had subsided. That space was helpful because we could reflect with more distance, and the scientific research was starting to be conclusive that the insects pose low risk to native hardwood trees and forests. Tree News is just one part of my practice, and I want to have time for other work as well. I’m trying to embrace it as a slow practice.

Tree News No. 5, Fall 2025, produced by Erin Mallea and Travis Mitzel.

You are currently based partially in State College and partially in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. What is the art scene like in Pittsburgh?

I moved to Pittsburgh in 2016 to attend Carnegie Mellon’s Visual Art MFA. I didn’t think I would live here for as long as I have to be honest. Pittsburgh is not a huge city, but there's an interesting and vibrant community of artists, musicians, and academics. There’s a large number of established museums and institutions given the city's size (in part due the city’s industrial-tycoon history). During and after grad school, I was able to build community and a good network of relationships and opportunities. There are a number of universities in Pittsburgh, and a lot of interesting, creative people coming to the city across different disciplines. The size and cost of living (though it’s getting more expensive) make starting things more accessible, whether artist-run spaces, experimental curatorial platforms, music venues, and DIY events or projects. Given the size you hit a ceiling of opportunities and funding eventually (artist funding is a challenge in Pittsburgh, and it’s going to get worse like everywhere across the United States with the administration’s massive cuts). It’s easy to have the “grass is always greener” feeling and compare it to friends in New York or LA, but so far it’s been a good homebase for me as an artist.

It’s a unique city. The topography, the dense green hillsides, the vernacular architecture. When it’s sunny, the city and light quality is really beautiful. The region has continued to be a source of inspiration for me as an artist: the industrial and extractive history, the booms and busts, the scars on and transformations to the landscape. One thing I appreciate about Pittsburgh is that the landscape is a constant reminder of human limitations and obvious falsehoods of American mythologies. While a lot has transformed since the steel industry shuttered in the 70s and 80s, that loss – living in the aftermath of a massive system collapse – is still seen and felt.

Compared to where I grew up, the plant life in Pittsburgh is really dense, green, and grows incredibly fast. Because the city is filled with ravines, cliffs and steep hillsides, many corners of the city are untamed and feel like wilderness. It’s an old city that experienced a large population decline, so there’s also a lot of aging infrastructure in need of repairs. I love the DIY things people (and the city) do as band-aids or temporary creative fixes. There’s a constant, visible tension between human infrastructure, natural forces and the effects of time. Deer in the middle of the neighborhood, hillsides you can never tame, electrical posts supporting one another with ratchet straps, and vacant buildings engulfed by vines. I appreciate that challenge to anthropocentrism – the feeling and reminder that human impact is fleeting, control is illusory and transformation is constant, even if slow.

What have you been working on recently?

In addition to my work at the Pittsburgh Glass Center, I recently made a new, expanded iteration of my work, Condition Report. It’s a delicate, hanging installation that visually references webs, nets, traps, tangled vines or brambles. The installation is made from second-hand jewelry chain, bronze and aluminum slag, glass and plastic beads, fishing sinkers, pennies, polyurethane foam and plastic nurdles I collected from the Ohio River, foam “stones” and spotted lantern flies encased in beeswax, shellac, resin, nail polish and sugar. Condition reports are documents that demarcate the state of objects in an archive or collection. The documents record change, inherited damage, alterations, and ultimately the object’s ascribed value. I was thinking of these documents in natural history collections specifically, where the “objects” are once-living things that evolved in complex ecosystems, or minerals and rocks that developed through particular conditions over millions of years. Referencing the study of natural history has been a recurring theme in my work, because you quickly get to the elephant(s) in the room: human-animals, the long human history of transforming and altering plants, animals and ecosystems (breeding, agriculture, global trade), and European colonial projects and their embedded value-systems and hierarchies.

Condition Report, installation view, every speck of dust illuminated, Tomayko Foundation, Pittsburgh, PA, 2025.

Photo Credit: Chris Uhren

Condition Report, detail, every speck of dust illuminated, Tomayko Foundation, Pittsburgh, PA, 2025. Photo Credit: Erin Mallea

Condition Report, detail, every speck of dust illuminated, Tomayko Foundation, Pittsburgh, PA, 2025. Photo Credit: Erin Mallea

I was trying to bring together different materials that speak to excess, exchange and use-value, afterlives of commodities, and residual materials, networks, and landscapes shaped or created by extraction. The work incorporates bronze and aluminum slag, impurities that are skimmed off during casting or manufacturing. I polished and added a patina to some of the slag – labor typically reserved for more valuable metals and precious objects. I was thinking of Pittsburgh’s industrial slag. The waste product from the region’s steel industry that was dumped into hot, glowing hillsides that now house subdivisions and dead malls. SLF arrived in the US on the global commodity chain – most likely on a stone shipment via container ship from China. The PR campaign to kill SLF is rooted in protecting agricultural commodities (wine and lumber). Condition Report incorporates pennies, which have been on the chopping block for many years because the production-cost exceeds their value. The installation includes pennies from the early 1960s to today. Their material composition has changed over the years from copper, to copper alloys, to bronze, to gilding metal, to today’s version: copper-plated zinc.

Condition Report includes a lot of small details. Nurdles are scattered throughout the work: small plastic pellets (think lentil-sized) that are melted down to produce plastic products. This raw material frequently spills in transit and is found in many waterways. I collected nurdles on the bank of the Ohio River in Beaver, PA downstream from the Shell Pennsylvania Petrochemicals Complex (Monaca, PA). The facility uses by-products of fracking to produce nurdles. There has been a lot of ongoing community conversation in Beaver and Pittsburgh about the plant. It was promoted as an economic savior for the region (a new steel-industry). Its supposed positive economic impact has largely been disproved. There have been consistent environmental and public health concerns since it opened. The plant is Pennsylvania’s second-biggest emitter of VOCs, and it released 95% of its annual emissions allowances in a single month before it began official operations in 2022. Since opening, the facility has repeatedly been in regulatory violation with a series of malfunctions and lawsuits.

Condition Report, detail, (___) / Blankspace, Pittsburgh, PA, 2024. Photo Credit: Sean Carroll.

I’m also interested in the layers of counterfeit, camouflage and mimicry through the materials. The jewelry chain is all second hand, and most of it is composed of mass-produced, inexpensive metals plated to look like gold or silver with imitation diamonds or precious stones. However, I included some gold-plated and more valuable metals in the mix. SLF are encased in caramelized sugar and look like they’re in amber. I covered other lanterflies in layers of gold or silver nail polish and bead-like pieces of poly-foam in nail polish and resin to look like pearls.

I wanted this web to have a density that rewards those who take a slow, close look. I like that it is composed of small elements with individual lives in intersecting systems before they became part of the work. The installation requires people to get close – almost inside the net – but some of the slag has barbs, and you can get caught. In fact, someone did get snagged at the busy opening.

Thank you so much for sharing your work and talking with us!

You can find out more about Erin Mallea and her work on her website.

You can find out more about Tree News here.

Blown glass, in progress Glass Center Residency, Pittsburgh, PA 2025.

Cast glass, in progress Glass Center Residency, Pittsburgh, PA 2025.